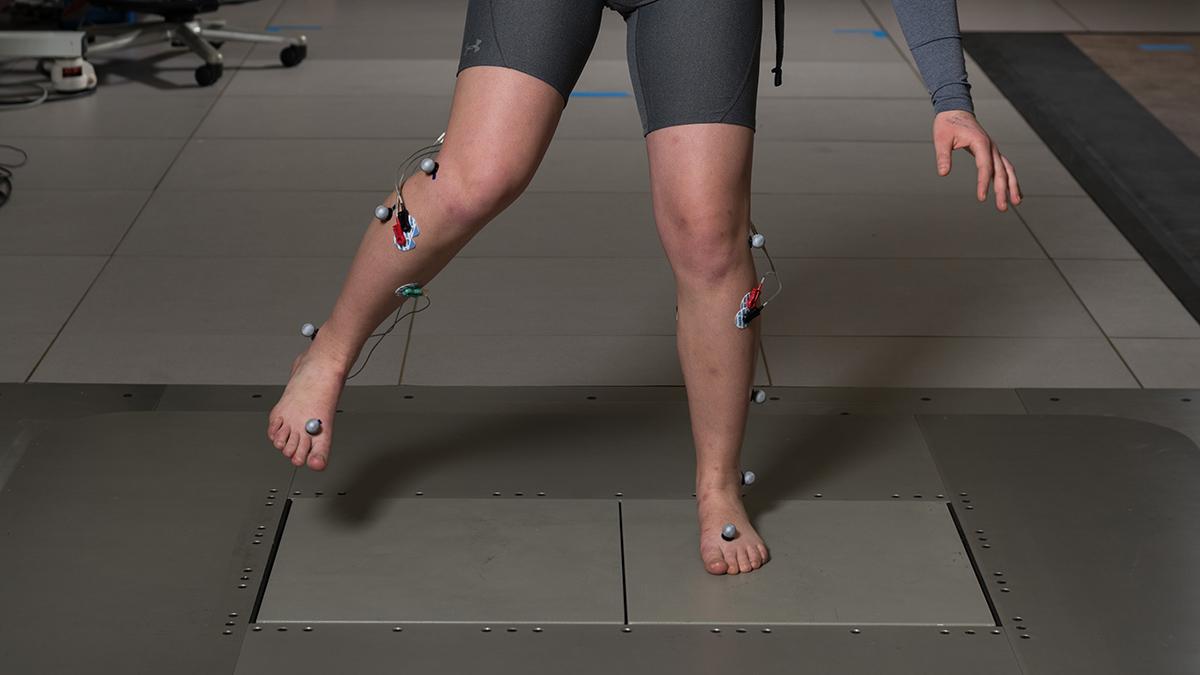

Researchers in Lena Ting’s lab use this shifting floor to literally pull the rug out from under people. No malice intended, of course; the idea is to study balance and brain activity. In one of those studies, recently published in Frontiers of Aging Neuroscience, the team documented that healthy adults with stiffer cognitive behaviors also have stiffer motor behaviors — even when they have no clinically diagnosed balance issues. (Photo: Rob Felt)

Researchers at Emory University and Georgia Tech have documented a connection between a higher-level brain function and balance control that may one day offer a sort of early warning for older adults that they’re at risk of developing balance problems or falling down.

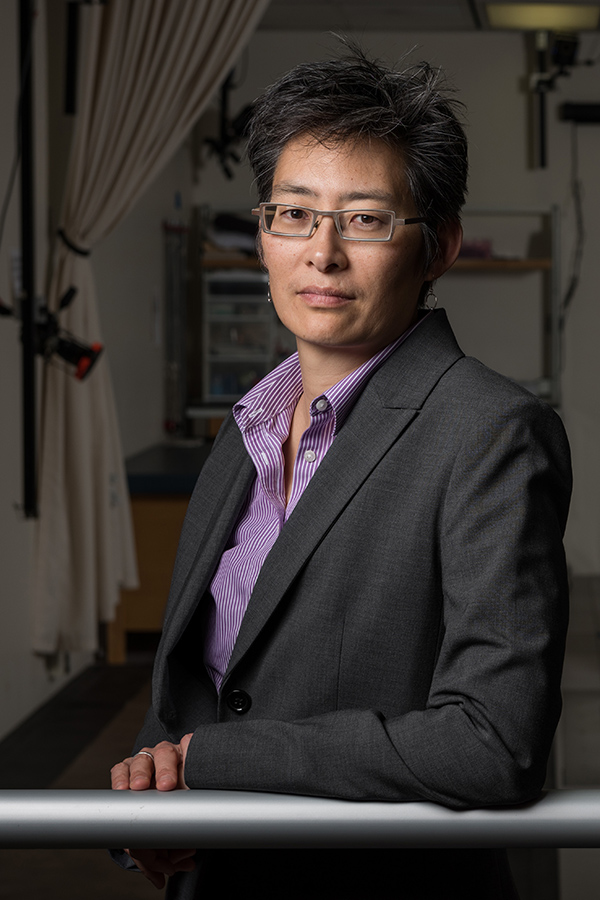

In a study published this month in the journal Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, the team led by Lena Ting observed that healthy adults with stiffer cognitive behaviors also have stiffer motor behaviors, as lead author and former Ph.D. student and postdoctoral researcher Aiden Payne has described it. Ting said the study subjects had no clinically diagnosed balance disorders, and the connection holds even accounting for natural differences in cognitive and balance capability between individuals.

“[This relationship] may be a way to kind of have an early indicator of people who may be at risk for falls but wouldn't get picked up on any type of clinical test,” said Ting, McCamish Foundation Distinguished Chair in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory and a professor in rehabilitation medicine in Emory’s Division of Physical Therapy. “So, if we want to do healthy aging and prevention of falling, then now would be the time to intervene to help these people maintain their faculties.”

Ting said people typically aren’t diagnosed with balance disorders until they’ve already fallen. Earlier warnings could allow time for interventions like exercise to help people maintain their motor and cognitive function.

In the study, the team tested individuals’ cognitive set-shifting skills, an executive function of that brain that allows us to change behavior between contexts. Then they put subjects on a moving platform and disrupted their balance — what researchers called “perturbations.”

They found people with poorer set-shifting ability also responded more aggressively to the loss of balance. Instead of only activating specific muscles to counter the platform’s shift and restore balance, these people activated opposing muscle groups, and their brain activity was more pronounced than those with better set-shifting skills.

“Their muscle activity is less specific; they're not responding in a way that's specific to the task,” Ting said. With lots of muscles moving, including groups that counteract each other, the participants stiffened their body overall instead of reacting only to the direction of the movement.

“They can't switch contextually, and so they're doing this behavior that helps them not have to guess or not have to actually figure out what's going on,” Ting said, “but ultimately, it's not good for your balance.”

In other words, their brains struggled to shift contexts with motor functions just as they showed reduced ability to shift contexts in thinking tasks.

Scientists have long observed a connection between declining cognitive function and an increased risk of falling down, though the specifics of the link remain foggy. Ting’s lab has published previous papers showing that impaired set shifting is associated with how frequently people have fallen in the past, including those with Parkinson’s disease, but this is the first time they’ve linked it to the potential for balance problems.

In addition to Payne and Ting, the study’s authors included Jacqueline Palmer, previously a postdoctoral fellow in Ting’s lab, and Lucas McKay, assistant professor in Emory’s Department of Biomedical Informatics and an expert in balance and falls.

Finding the early “pre-clinical” connection in their data was a bit of a happy accident: The participants were actually part of a control group for a Parkinson’s study — remember, these were older adults with fairly good balance and no cognitive problems. There’s more study needed to turn the link into true preventative medicine, but Ting said it could be a promising way to track brain health.

“What's their brain health, and how close are they to getting to the point where things might start declining in a noticeable way? The brain is really plastic, so things will decline, but they might not show up behaviorally for some time because people are able to compensate,” she said.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant Nos. R01 HD46922, F32 HD096816, P50 NS 098685, and UL1 TR000424; the Fulton County Elder Health Scholarship; and the Zebrowitz Award. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any funding agency.

Latest BME News

Jo honored for his impact on science and mentorship

The department rises to the top in biomedical engineering programs for undergraduate education.

Commercialization program in Coulter BME announces project teams who will receive support to get their research to market.

Courses in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering are being reformatted to incorporate AI and machine learning so students are prepared for a data-driven biotech sector.

Influenced by her mother's journey in engineering, Sriya Surapaneni hopes to inspire other young women in the field.

Coulter BME Professor Earns Tenure, Eyes Future of Innovation in Health and Medicine

The grant will fund the development of cutting-edge technology that could detect colorectal cancer through a simple breath test

The surgical support device landed Coulter BME its 4th consecutive win for the College of Engineering competition.