Hands-on approach to teaching microfluidics is inspiring future innovators

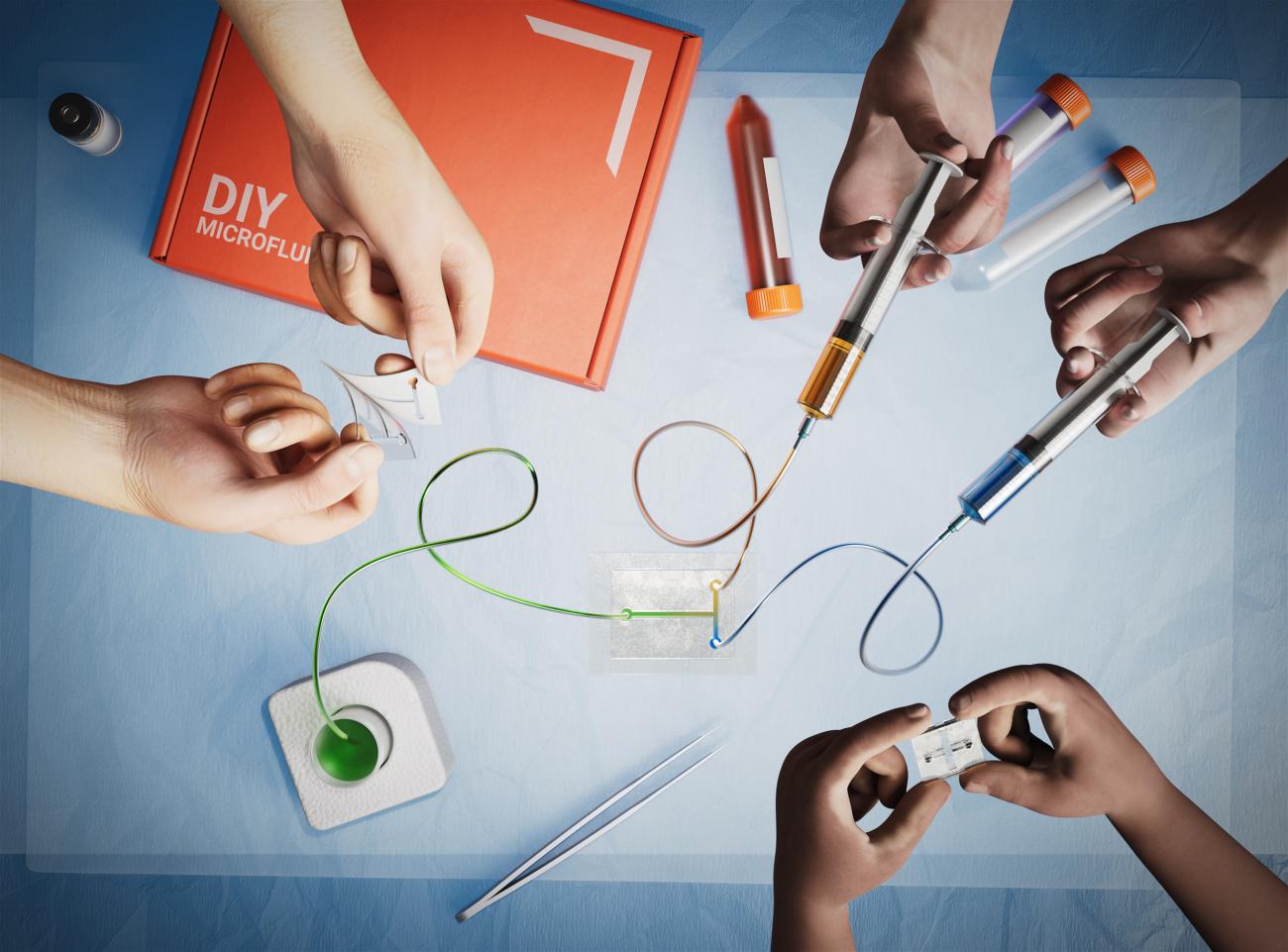

Students in David Myers' class on translational microsystems build and test microfluidics kits. Watch a video on how they do it.

By Jerry Grillo

In the movies, Ant-Man can shrink down to the size of an insect to carry out his superhero missions. It makes for fun cinema, but of course, it is impossible. For starters, biological systems can’t scale up or down and stay proportional. The hero would die before throwing his first teeny, tiny punch.

That’s miniaturization science for you. It’s the study of how materials and systems behave at microscopic scales, and it’s transforming biomedical engineering. And though it has led to breakthroughs in diagnostics and treatments, “teaching students about the subject is really challenging,” said David Myers, assistant professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory.

“It’s because the behavior of fluids and materials at such small scales defies intuition, and you can’t really observe what’s going on,” added Myers, who understands the instructional challenge well — he teaches a graduate level course focused on translational microsystems, which is heavily integrated with his lab’s research.

Recognizing the limitations of traditional coursework, Myers and his collaborators have developed a different approach. In Myers’ class, students build and test and observe the workings of microfluidic devices, a hallmark of miniaturization science — microfluidics is the manipulation of tiny volumes of fluids in miniaturized devices.

Their new approach has made all the difference, even earning Myers a CIOS Award for teaching excellence. But Myers is quick to emphasize that this was a team effort. He and his lab developed a hands-on activity to help students learn device construction (and the underlying technical concepts).

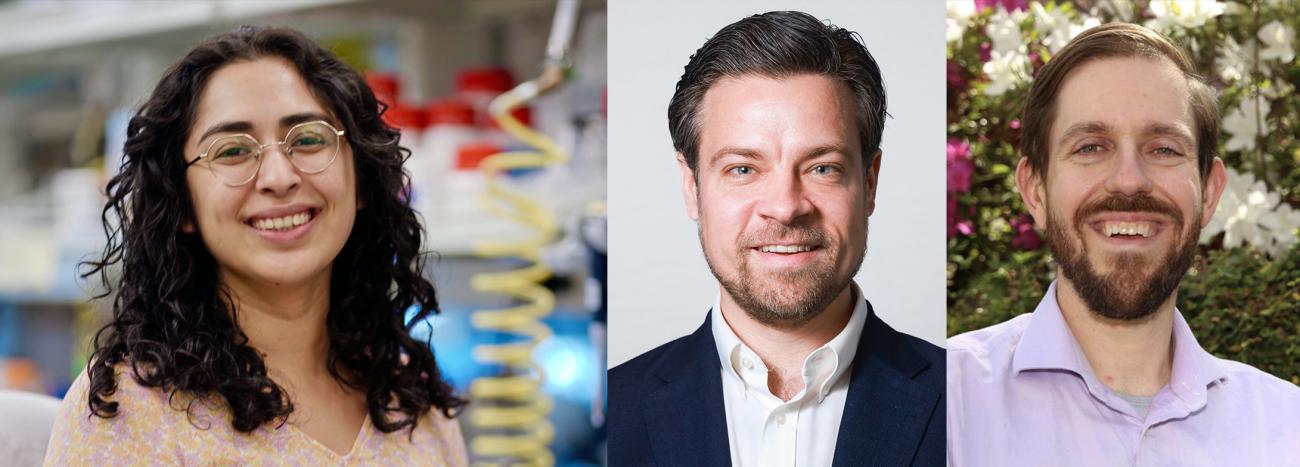

Then he reached out to Todd Fernandez, senior lecturer and Coulter BME’s director of learning innovation. Together they optimized the activity to maximize students’ learning. That has evolved into an ongoing partnership between technical and educational research faculty in the department, resulting in an article in the journal Lab on a Chip.

"In other microfluidics courses, you walk through the step-by-step process of fabrication, but actually seeing the device come together in front of you provides such valuable insight into the underlying concepts and manufacturing techniques,” explained Priscilla Delgado, a fifth-year graduate student in Myers’ lab and lead author of the published study. “That hands-on experience is crucial for truly understanding this technology."

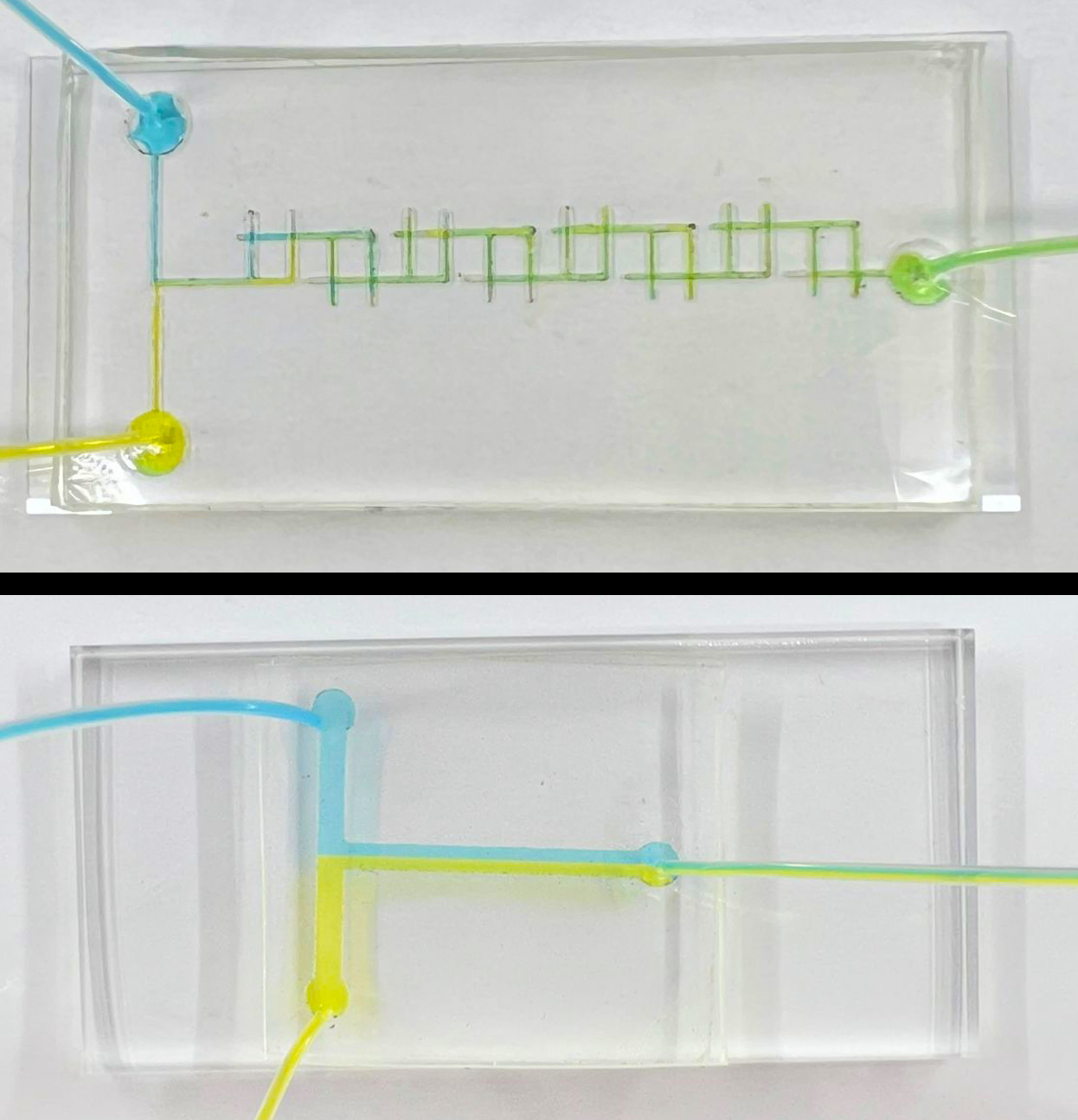

Diffusion plays a large role in microscale mixing. Shown are two mixers: F-mixer (top) and a T-mixer (bottom) are mixing blue and yellow fluids. An F-mixer achieves better mixing by splitting and recombining the fluid in each F. In a T-mixer the fluids are not split and recombined, and therefore have a smaller interfacial area — depending on the fluid flow rate (as shown in the picture), this results in the two streams seemingly staying separate.

Bridging Critical Gaps

Myers’ course bridges several critical gaps, including the high cost of advanced learning activities. It also addresses student misconceptions.

“The primary objective isn’t just the successful construction of devices, but a deeper conceptual understanding of miniaturization science and design principles,” said Myers, whose approach emphasizes conceptual change.

Students often come into the course with misunderstandings about microscale phenomena, “assuming that fluid flow at this scale behaves the same way as in larger systems,” Myers said.

Delgado added, “but it’s wild how fluid behavior changes at the microscale. If you mix two colored liquids in a regular cup, you get a third color. But in microfluidics, the laminar flow and reliance on diffusion can keep those streams separate — it really challenges your intuition about mixing.”

The class allows students to build and test microfluidic kits — mixers, valves, and bubble generators, using inexpensive, widely available materials. This activity is structured to help students encounter misunderstandings and work through them. Rather than just presenting correct information, the instructors guide students through a learning cycle, identifying errors, reflecting on the mistakes, and ultimately, honing their understanding.

“You can see their brains just sizzle,” said Myers. “Then you kind of add a little bit of structure. You ask, ‘Are you sure you have all the layers there that you’re thinking about?’ And then they’ll go back, count, and realize—oh, there’s this missing middle layer.”

The layer-by-layer assembly technique uses laser-cut adhesive films to construct microfluidic devices. Because the devices are assembled from transparent layers, students can see how their designs function and they can troubleshoot any errors.

“One of the best things about these sticker-based microfluidic devices is how easy they are to prototype,” said Delgado. “I can literally have a new design laser-cut and assembled within an hour, rather than waiting months using traditional methods. The accessibility and speed of iteration is a game-changer."

Expanding the Possibilities

Beyond its accessibility, the sticker-based microfluidic approach also expands the possibilities for innovation.

“The really cool thing is, this is a sticker,” Myers said. “You can place it on your skin. You can place it on the table. You can place it on the wall, if you really felt like it. And when you integrate it with high-end instrumentation like advanced sensors, suddenly you have a resource that traditional microfluidics can’t easily replicate.”

This kind of flexibility enables students to explore microfluidics in new ways. The study involved 57 students, some of whom took their designs beyond the classroom.

“I cannot say enough how much I love how accessible it is and the portability of it,” Delgado said. “You can do this anywhere. You could do this at home. We’ve done it at science fairs for high school students to really challenge the way they think about mixing.”

The impact of the work has also influenced the direction Delgado wants to take in her career. She’s found herself drawn deeper into the field, inspired by microfluidic design.

“The first time I laid eyes on that microfluidic device I had just built, I was captivated,” she said. “I remember thinking, ‘This is so cool; I have to dive deeper into this field.’ That’s when I knew a PhD was in my future, even though I had initially planned otherwise.”

This approach to teaching miniaturization science not only enhances learning but also democratizes access to innovation, according to Myers.

“The really cool thing that I love about this activity is that you’re sharing knowledge and power with the people using the technology,” he said. “Instead of them receiving technology from some high-resource institution, they’re able to look at the problems and start addressing them themselves.”

Miniaturization science plays a crucial role in developing point-of-care medical devices and other low-cost diagnostic tools, particularly in resource-limited settings. Equipping students around the world with the ability to create microfluidic systems could help empower future researchers and engineers.

Fernandez believes this hands-on approach represents a shift in how miniaturization science will be taught.

“By focusing on student-driven exploration and conceptual understanding rather than rote device assembly, educators can better prepare the next generation of engineers and scientists to navigate and contribute to the ever-expanding world of microsystems,” he said. “ And what’s really cool is, you let them play, and they learn more. They discover things that we didn’t even have time to teach them.”

Latest BME News

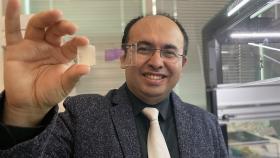

Jo honored for his impact on science and mentorship

The department rises to the top in biomedical engineering programs for undergraduate education.

Commercialization program in Coulter BME announces project teams who will receive support to get their research to market.

Courses in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering are being reformatted to incorporate AI and machine learning so students are prepared for a data-driven biotech sector.

Influenced by her mother's journey in engineering, Sriya Surapaneni hopes to inspire other young women in the field.

Coulter BME Professor Earns Tenure, Eyes Future of Innovation in Health and Medicine

The grant will fund the development of cutting-edge technology that could detect colorectal cancer through a simple breath test

The surgical support device landed Coulter BME its 4th consecutive win for the College of Engineering competition.